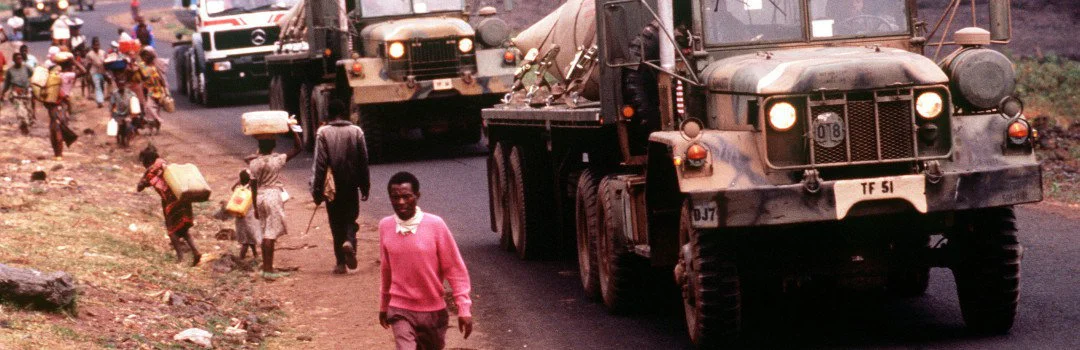

The Rwandan genocide is one of the great human cataclysms of the twentieth century. The genocide was a “systemic and coordinated attempt to physically eliminate the entire Tutsi population of Rwanda.” The most accurate figure for those who were killed in the 1959 genocide, when Hutus seized power and stripped Tutsis of their lands, was 100.00. In 1994, the mortality figures were more immense; 800,000 Rwandese, including moderate Hutu and Tutsi, were killed in the space of 100 days at the hands of Hutu militia and the army. It was the fastest genocide in the history of humanity. This genocide cannot be explained through stereotypes; the actors are far from just “savages”, “barbaric”, mindlessly killing. Although their actions are abhorrent, they are breathing and thinking Homines sapientes who had political motives. How can one explain the Rwandan genocide? Some European commentators had an answer. The trigger that came in 1994 is a product of a deep history. They argue, “African tribes are possessed by ancestral hatreds and periodically slaughter each other because it is in their nature to do so.” In order to deeply grasp the human catastrophe that consumed Rwanda, this paper will analyze the complexity of the contested Rwanda histories of ethnic relationships and the role of a strong state in Rwanda. There are some factors that should be taken into account such as: the pervasive economic crisis, the politicization of both ethnicities, Hutu and Tutsi under the Belgian rule as well as in the independence era in 1959, and the strength of the Rwandan state. I will argue that a strong state, weak ethnicity and the economic situation have led to the Rwanda genocide in 1959 and 1994.

Post-Conflict in Liberia and Crime in Monrovia

Although crime has existed since antiquity, with piracy and slavery, we can no longer assume that a crime committed here and now is an isolated or local incident since we can no longer have this simplicity in today’s complex world. To elaborate, the crime that are seen as local or regional have become relative. The examples of crimes vary widely; they can include drug distribution, homicide, human trafficking and kidnapping. In order to have a critical examination of crimes in post-conflict societies, which is the “no peace, no war” or “neither peace, nor war” situations after the signing of peace accords, it is first essential to understand the nature of conflict. In post-conflict Liberia, there are numerous research topics about Liberia that can be classified under the umbrella of broad categories: civil wars, war crimes and Charles Taylor. One of the main reasons Liberia attracted the attention of the world is because of the atrocities committed during the civil wars. Nevertheless, criminology, as an academic discipline, has not yet strongly emerged in Liberia. What is peculiar and unique in the case of Liberia, in which I will investigate, is the potential in returning the country to war through the involvement of ex-combatants in crime. This makes criminality in post-conflict Liberia a source of serious concern.

Imperialism, Capitalism and Mozambique

In order to grasp the causes of African underdevelopment, one should examine colonial rule in the wider context of European economic power over Africa. In the eighteenth century, the relationships between Europeans and Africans beginning with the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade led to the continent’s underdevelopment. Africans were free people until the advent of slavery when they became Africa’s main export. Slave trade refers to the captive and shipment of Africans against their will to numerous parts of the world. They lived and worked as property of the European colonists. In the ninetieth century, the structure and development of the world capitalist system consolidated the underdeveloped structures of Mozambique. The status of Europe and its penetration changed from a source of demand for manpower, particularly slaves, to a source of supply of raw material. Although the colonial rule that began in the early nineteenth century has disappeared since 1975, its impact or outcome has been increasing steadily in Mozambique. In this paper, I will analyze the underdevelopment of Mozambique as a result of colonial rule during the imposition of Cotton Regime (1938-1961). More specifically, what has been the impact of colonialism on the political economy of Mozambique?

Greed and Grivance in Sierra Leona

The twentieth century has witnessed a remarkable rise in armed conflicts that are most likely to occur in a weak state as well as a poor country. Furthermore, the rise of “new” non-state actors such as, organized criminal gangs, religious groups, mercenaries, ethnic militias and private security companies are widely recognized. ‘New War’ involves an apparent blurring of the boundaries among struggle for economic and political ends (war) and the force used for private material gain (criminal violence). In the light of the criminal motivations, the civil war in Sierra Leone (1991-2002) is an example of a recent complex conflict, amenable to both grievance and greed-based explanation. My position is that, although the violence is in part a reaction to political repression, the drive to possess the country’s valuable resource of diamond explains more convincingly the conflict. In this paper, I will argue that the greed theory is more convincing than the grievance theory in this period of “new wars”.